Understanding healthcare through human factors

‘When people go to work, 99.9% of the time they set out to do a good job. So if they aren’t following the procedures they’re not being malicious: the procedures might be wrong or they might not have the resources to do that.’ Dr Vicky Jones, associate medical director for safety and learning at North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust is describing human factors principles – an approach that that analyses human behaviour in the context of wider influencing factors.

‘I’m responsible for looking at patient safety issues, responding to them, and using the information from good and bad events, to spread learning across the organisation,’ explains Vicky. ‘In the past, we often tried to implement solutions without understanding how people work. So, in our serious incident investigations, lots of the actions were “Remind people to do the thing they’re supposed to be doing” without an appreciation of why they hadn’t been doing it in the past,’ says Vicky. ‘Using human factors principles means working with the inherent nature of humans rather than trying to work against it.’

“We’re understanding each other as people rather than expecting people to be like robots.”

Aware of the potential benefits, in 2017 Vicky and three colleagues (Vikki Howarth, Wai Yoong and Dr Gopakumar Sudhir) applied for UCLPartners’ human factors programme. This involved a week-long training course, followed by 10 months of support including workshops, site visits with 1:1 coaching and access to a network of like-minded professionals. The programme was delivered in partnership with MedLed Ltd, specialists in Human Factors and Performance Science. Vicky and her colleagues joined teams from Essex Hospitals, the London Ambulance Service and University College London Hospital.

‘We managed to achieve quite a lot, partly through our enthusiasm and partly through our organisation being very receptive to the ideas,’ says Vicky. The team implemented changes in a host of areas. Examples included streamlining forms to make them easier to complete; adopting a new type of needle to prevent medical errors; designing a patient safety walkabout programme and changing the sepsis pathway to help escalate treatment.

Since participating in the human factors programme Vicky and her colleagues have trained 350 staff in North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust to use the principles they were taught.

Cardiac arrest

One successful initiative is a new a ‘cardiac arrest at hospital’ night huddle. ‘Because of the number of team members holding the cardiac arrest beep, often a team would have never met until the first cardiac arrest they attended,’ explains Vicky. ‘That meant they didn’t know each other’s competency levels, so a team member might have very advanced skills in managing a patient’s airway, or they might need to do some procedures under supervision due to their level of training.’

Now that the team meets every evening for a quick meeting, these problems have been resolved. The huddles help build the team, too, says Vicky: ‘Trust is really important, especially for junior doctors who often find cardiac arrest quite a daunting experience.’ Overall, the new system allows for better planning, allowing the process to run more smoothly, with a better chance of a good patient outcome.

Learning from Excellence

The team also used human factors to embed its Learning from Excellence programme across the Trust. ‘Healthcare tends to concentrate the majority of our learning on things that go wrong,’ explains Vicky, ‘and we very rarely look at things that go really well. But if you ignore that, you’re missing out on a huge amount of useful learning.’

Learning from Excellence turns that approach on its head, focusing on what worked well, and trying to replicate that. To take part, staff nominate a colleague, describing precisely what they did well on a given occasion. Every few weeks, the Trust pulls together all the nominations across a department and runs a feedback meeting, analysing themes and trends. The nominee receives a certificate, which they can use for their e-portfolio or appraisal. ‘It’s great for morale,’ says Vicky, ‘and it helps people learn how to improve because if you’re complimented on a particular aspect of your care, you’re more likely to do it again. And if it’s shared, others can learn from that too.’ The programme had been launched back in 2016, but the human factors work helped it spread across the organisation. ‘We launched it in the paediatric department and little projects were bubbling up in other departments, but we didn’t have a cohesive structure,’ says Vicky. ‘Now, it’s an agenda item on each department’s clinical governance meeting and that feeds up to our divisional level, and then also to our trust-wide safety and outcomes meeting. It’s become part of our risk and governance strategy.’

Just culture

The Learning for Excellence scheme is one example of how the human factors work is combining to influence overall culture. Another is a growing focus on the principle of ‘just culture’. This involves accepting that mistakes are a normal part of human activity, and that an organisation can only learn and improve if it understands how the system around the person fed into that mistake.

‘If you looked at our serious incident investigations, a couple of years ago, an incident might have been attributed to ‘human error’, says Vicky. ‘But now, we would never stop at that – we would ask “How did the circumstances allow that error to be made? What safety measures were in place to prevent a human error leading to an incident? What can we do to improve these for next time?” We’re understanding each other as people rather than expecting people to be like robots.’

This is filtering down into their HR processes too: ‘When there is a problem, if you simply discipline or sack someone, you never find out why the decision made sense to them at that time and achieve the learning about the wider system.’

The changes are expected to improve organisational performance – but are already showing an impact on morale. ‘In our staff survey, we were the second-most improved trust this year, and I think the human factors programme has really helped with that.’ For Vicky, this approach is now central to the way she approaches her work: ‘Learning about human factors has changed my practice more than anything I’ve done as a doctor.’ It’s made me re-evaluate a lot of my preconceptions so I can better judge situations and make improvements that are more likely to work – particularly in the safety arena.’

“Learning about human factors has changed my practice more than anything I’ve done as a doctor.”

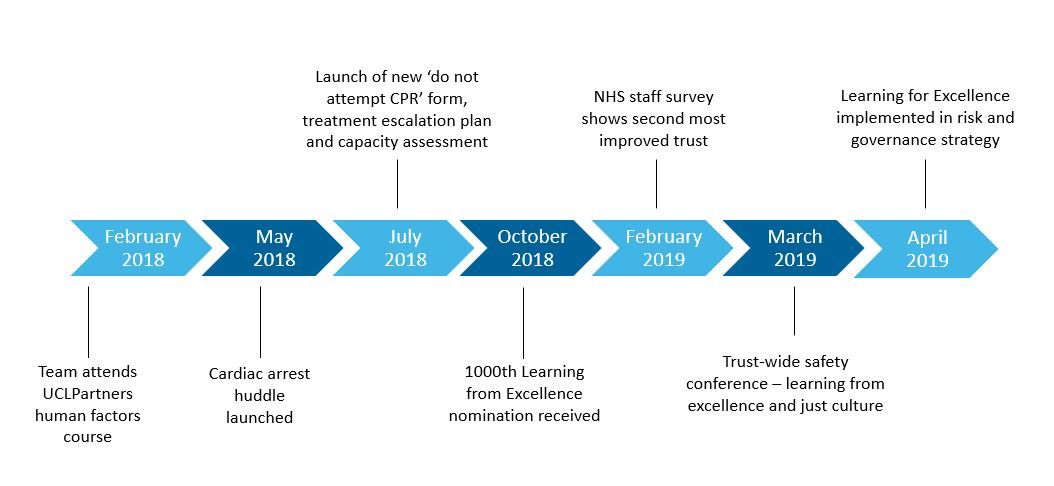

Project timeline