Monitoring wellbeing through phone use

When someone with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or psychosis has a relapse, they may be hospitalised, perhaps forced to take time off from work or caring duties – essentially, life may be put on hold for them and their loved ones. But if there was a warning system, something that could alert the mental health team that someone was on the verge of relapse, perhaps they could prevent a distressing episode from happening.

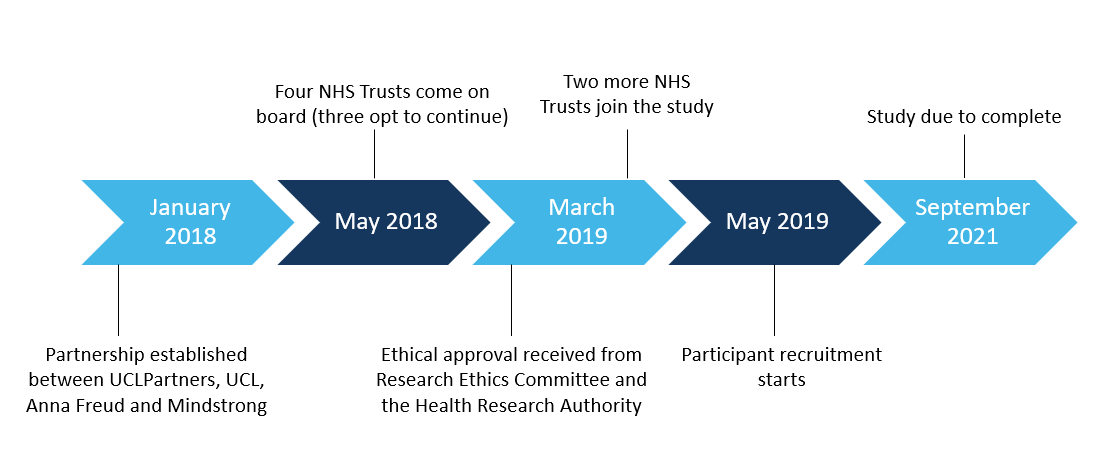

That is exactly the vision that a team at the Anna Freud Institute is hoping to realise, alongside US company Mindstrong, in a research project called REST (relapse evaluation using smartphone technology), supported by UCLPartners.

The tool centres on an algorithm that Mindstrong has developed via a phone app that tracks the way people use their phones. ‘It doesn’t look at the content of what you’re doing, such as what you’re writing in your email,’ says project lead Alisa Anokhina. ‘Instead, it tracks what times of day you’re using your phone, how often you are making phone calls, sending text messages and receiving them, and things like orientation, acceleration, taps and swipes.’

This produces huge amounts of data, which pilot studies have analysed to identify and correlate behavioural patterns, using a technique called digital phenotyping. These patterns are then matched to existing psychological measures – for example, of memory or attention. And these measures, in turn, can correlate with psychological wellbeing.

The project will involve loading the app onto the phones of individuals with a history of severe mental illness and tracking, for about a year, how they use their phones and whether or not they’ve had a relapse. Then the analysts will examine the data to see whether anything changes in people’s phone use weeks and days before relapse. This will help them identify signs that could predict relapse in others, which could then trigger some kind of pre-emptive intervention.

So, what would this pre-emptive intervention look like? ‘It’s very early days,’ cautions Alisa. ‘But if it did work, and if the patient wanted this feature, the system could automatically alert your primary care or crisis team, or you could have a virtual nurse that pops up on your phone and says “Hey, is everything okay?”’

Another benefit may be improved reliability. Even if mental health services had the resources to monitor their clients weekly or daily, people do not always share how they are really feeling, and might not pick up the phone if they are unwell or don’t want to talk to someone. In contrast, REST is passive. It requires no active input from the user – they just use their phone as they normally would, so the data will be accurate. It requires no input from the clinical team, either, but they know they will receive an alert if something is wrong. The next step will involve recruiting around 400 people receiving treatment at different London mental health services, who have had a relapse in the previous three months. Patients can uninstall the app from their phone whenever they want, so they hold ultimate control. ‘We wondered if people might be quite resistant to being involved,’ says Alisa. ‘We abide by data protection, and everything is anonymous and secured and encrypted, but the idea of an app tracking you on your phone still could sound scary. But actually, in the pilot studies people were really receptive to this. So, we’ll see how it goes.’

This project forms part of our work on healthcare innovations that use data or artificial intelligence to improve care for mental health. Our clinical research networks, wider networking activities and understanding of improvement help connect people and steer projects from early research through raising awareness and, ultimately, spread.