Cardiovascular disease accounts for a quarter of premature deaths in England, drives a large proportion of urgent and emergency care, and explains a fifth of the life expectancy gap between most and least deprived communities. It is also very preventable.

Much cardiovascular disease is caused by high impact conditions like blood pressure and cholesterol, diabetes and chronic kidney disease. These are highly modifiable risk factors where treatment in routine primary care is very effective at preventing heart attacks and strokes.

Despite this, many people with these conditions are not on optimal preventive therapy – for example three in 10 people with hypertension are not treated to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommended target; one in five people with established CVD are not being prescribed life saving treatment to lower their cholesterol; and there is widespread geographical variation in treatment levels that fuels health inequalities.

In England we have tolerated these high levels of undertreatment and variation as the norm for decades. Despite regularly updated NICE guidance, national levers such as the quality and outcomes framework, and widespread deployment of local incentive and quality improvement programmes, there has been little more that incremental improvement over many years. As a medical student I was taught the rule of halves for high blood pressure (we diagnose 50 per cent of hypertensives and we optimise treatment in 50 per cent). Decades later and even before the disruption to services caused by the covid, we still had almost a third of our patients with hypertension not treated to target. And since the pandemic, despite the universal focus on transformation, blood pressure optimisation rates have still not returned to the far from ideal pre-pandemic levels.

Size of the Prize

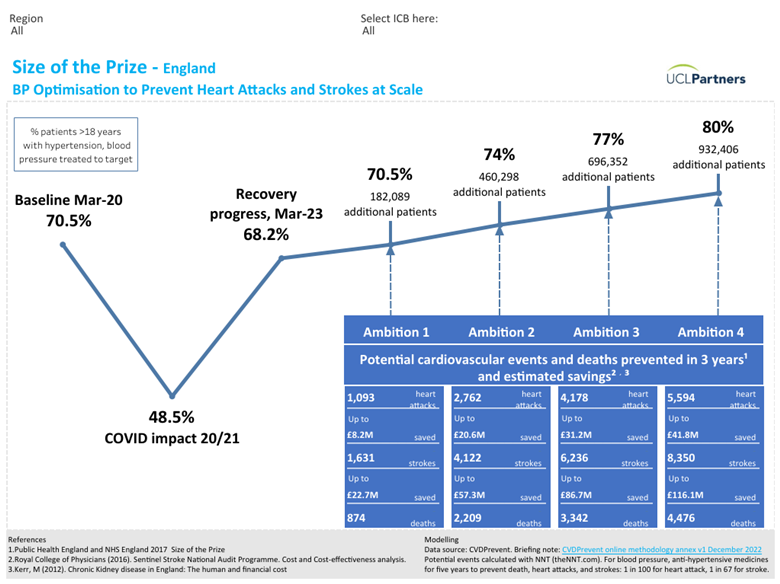

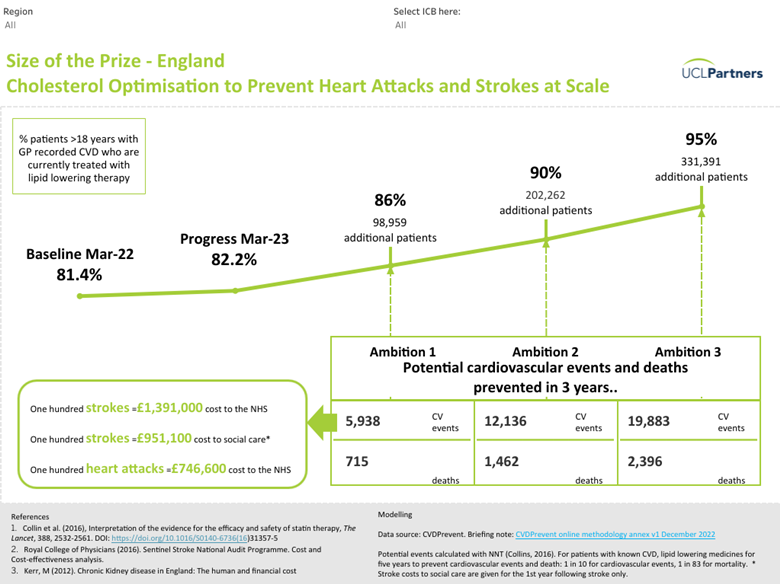

The UCLPartners Size of the Prize shows the magnitude of the opportunity for CVD prevention. If blood pressure optimisation rates across England were improved from the current 68 per cent to 80 per cent, we would prevent an extra 14,000 heart attacks and strokes in 3 years, saving the NHS around £150m, driving down emergency admissions to hospital and taking pressure off hospital waiting lists and GP services. If we increased to 90 per cent, the number of people with pre-existing CVD who are treated with a statin, we would prevent 12,000 heart attacks and strokes and 1,400 deaths, with similar reduction in health care demand. This would bring huge population health benefit in a short time frame.

These are realistic ambitions, but to achieve them we need a step change in our approach to preventive care. We are awash with population health data that re-iterates “what” needs to be done. In granular detail, CVDprevent (the national primary care audit) shows practices and primary care networks where the gaps, inequalities and opportunities are – for example how many patients with hypertension, CKD or diabetes are not treated to target. The “what” is clear: we need to get much better at optimising preventive treatment. Our challenge is to understand the “how” – how to translate these insights into action in real world primary care, action that will see patient care optimised at scale, and heart attacks and strokes prevented by the thousands.

We need to focus on the ‘How’, not just the ‘What’

Routine recall and review is at the heart of long-term condition management in primary care. But the current model of care, determining who to review and when, is designed to meet QOF targets. It does not prioritise and optimise treatment in those at greatest risk for maximal individual and population health benefit. QOF reviews are bread and butter for primary care. Where this functions well it may support incremental improvement, but it will not deliver at-scale optimisation.

Achieving a step change in CVD prevention – to prevent thousands of cardiovascular events in 3 years – will require a focus on the “how” of translating data to action. To deliver at-scale population health impact will need at-scale case finding to identify patients with high-risk conditions who are on suboptimal treatment – followed by systematic steps to optimise their care and reduce their risk.

And for the data to be actionable in the real world, the case finding needs to be focused on key indicators of cardiovascular risk across the high impact conditions like blood pressure and cholesterol, diabetes and CKD. And the data needs to be presented in a way that allows primary care clinicians to stratify and prioritise – so that they can ensure manageable workload while improving outcomes for their patients.

CVDACTION is a new free tool that has been built for this purpose. It mirrors CVDprevent and in addition identifies individual patients for GPs so that treatment can be optimised. It also enables prioritisation and phasing of work over time, incorporates co-morbidity so that multiple risk factors can be addressed in individuals (holistic care is good for patients and efficient for clinicians), and filters data to support targeted action on health inequalities. CVDACTION is about to be trialled, together with implementation support, in a number of primary care networks in London and elsewhere. Rapid evaluation will answer 2 critical questions:

1. Does targeted case finding for people at high risk of cardiovascular disease lead to a step change in optimisation rates and therefore a step change in expected population health impact?

2. What support needs to be in place in the real world for primary care teams to use and act on case finding data – reflecting Claire Fuller’s challenge that ambitions for primary care will not be realised without resources and infrastructure to support implementation on the ground.

It is time for the NHS to challenge our longstanding tolerance of sub optimal treatment in the prevention of heart attacks and strokes. Transforming the management of high impact conditions in primary care is not an intractable problem. It just requires smarter use of data and support for GPs and their teams to do things differently in response to the data.

Originally published in HSJ.